Gregory Dexter: A Controversial Man in London and Pawtuxet

A Small Chapter in New England's History

Below is an article I wrote for The Pawtuxet Village Association’s newsletter, The Bridge, which originally appeared in two separate issues, Spring 2020 and Fall/Winter 2020. I have been a regular contributor of articles and poems to the newsletter since 1985.

If you’re unfamiliar with Rhode Island, the smallest U.S. State, Pawtuxet Village spans the north and south banks of the Rhode Island’s Pawtuxet River where the river flows into Narragansett Bay. The northern shore is in the city of Cranston and the southern shore is in the city of Warwick.

Dexter’s story is also personal since I am a descendant of Gregory Dexter through my mother and through Dexter’s son John. In the genealogy of the Dexter family compiled in 1857 by S. C. Newman and printed in 1859, Dexter was born in Olney, Northhampton, England in 1610, but according to a grandson, Dexter claimed he was born in London. Bradford F. Swan, who wrote Gregory Dexter of London and New England, notes that the exact location of Dexter’s birth is clouded in the mist of history. However, Dexter’s father hailed from Olney and was buried there. There is no record of when Dexter and wife Abigail (née Fullerton — no relation to me, which is another story) married, only that they arrived in Rhode Island in 1644. The marriage produced five children — four sons and a daughter, all born in Providence.

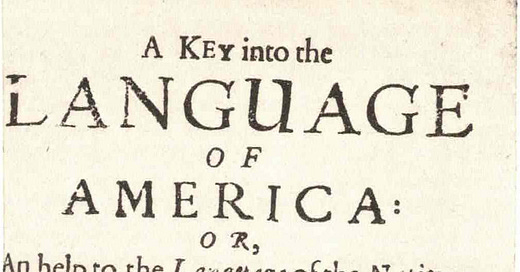

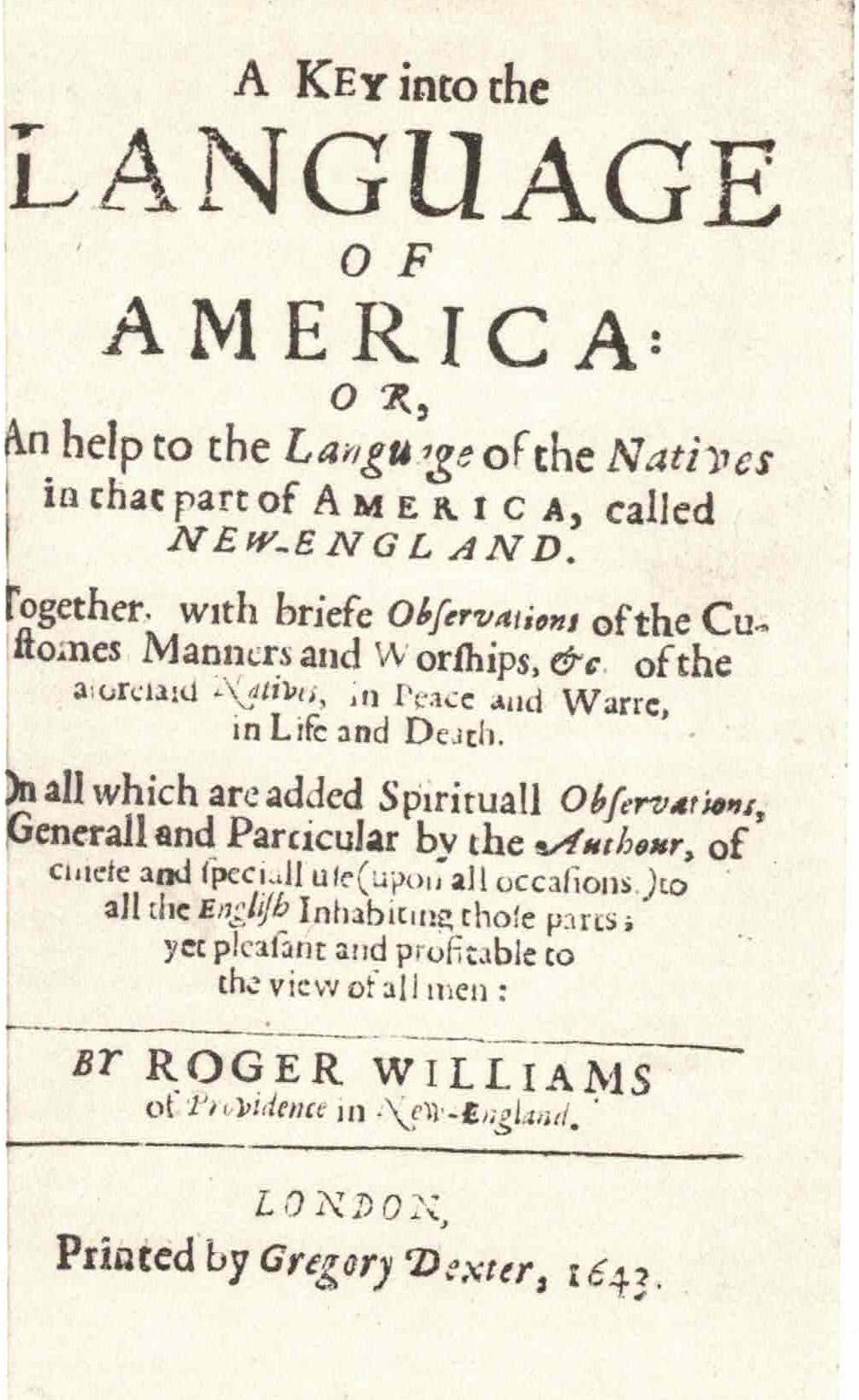

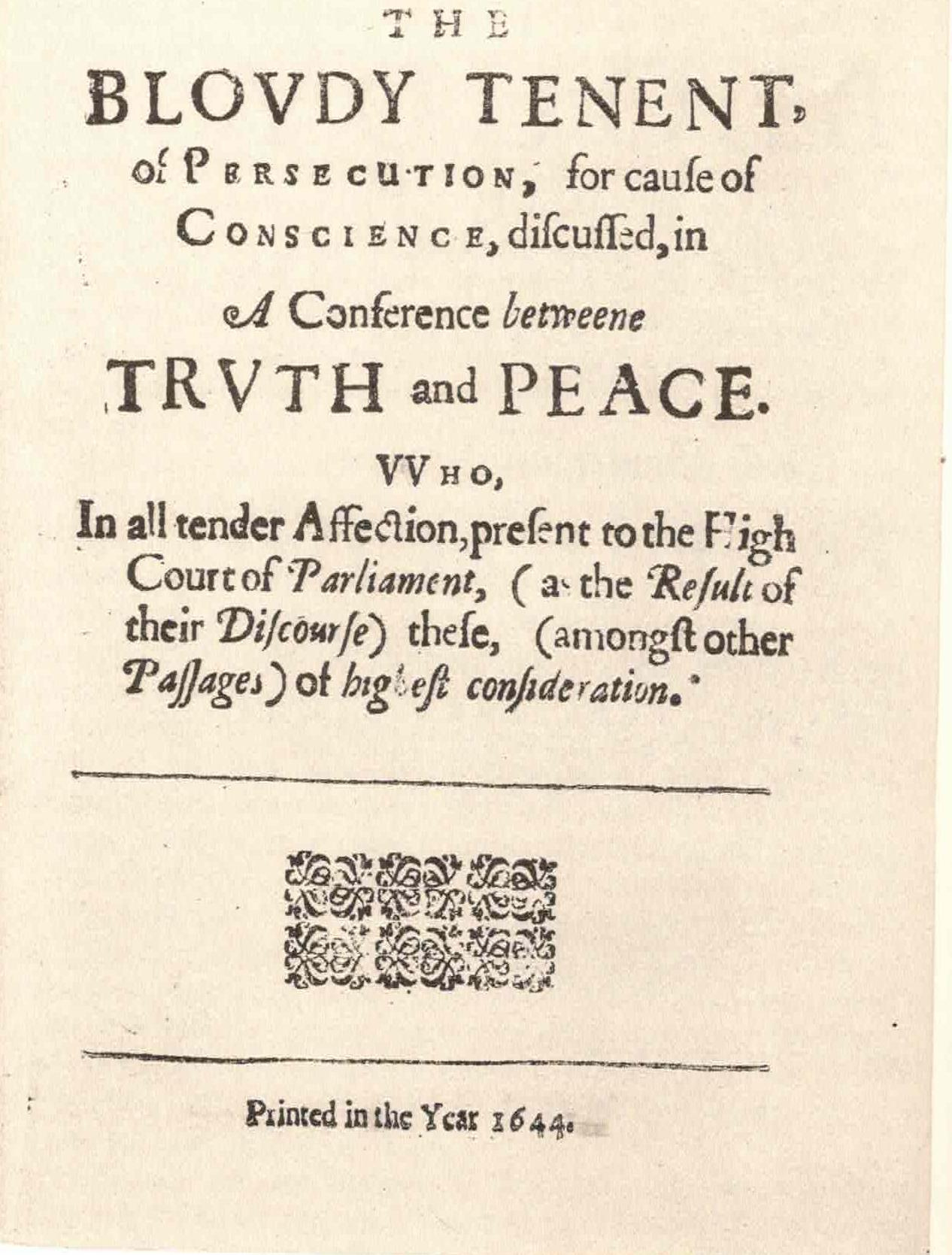

The images below are from the book Gregory Dexter of London and New England by Bradford F. Swan.

Part One

Unless you’re familiar with 17th-century colonial Rhode Island history, you’ve probably never heard of Gregory Dexter. An arguably controversial figure who played diverse roles during his long life, he was a well-known printer in London and later held numerous civil positions in Rhode Island’s colonial government. He was both an idealist and an activist who held strong views about government and religion and was not shy about voicing his views or acting on them.

Dexter began his career as a printer’s apprentice in 1632. During this time, he gained some notoriety by collaborating in printing “secret” publications critical of Charles I and the Church of England. This activity almost landed him in jail after he was indicted with two others in 1637 for printing pamphlets written by William Prynne, a controversial Puritan polemicist and pamphleteer already imprisoned at the time. Although threatened with prison, Dexter escaped sentencing with a censure.

After completing his apprenticeship, in 1639, Dexter joined in a partnership with Richard Oulton, possibly in 1641, when their names appeared as joint printers of two tracts by John Milton: Of Prelatical Episcopy and Of Reformation Touching Church-Discipline in England: And the Causes that Hitherto Have Hindered It.

Dexter's partnership with Oulton ended in 1643, but it’s unknown whether Oulton quit the business or died. By that time, Dexter’s name had already appeared in publications without Oulton’s. He printed diverse texts by New England Puritan clergy as well as by British religious and political authors. Among these was Roger Williams’ book A Key into the Language of America, printed in 1643.

Williams had traveled to London in 1643, not only to collaborate with Dexter in printing his books, A Key into the Language of America and The Bloudy Tenet, but also to secure a “Patent,” which would enable the citizens of Providence, Portsmouth, and Newport to form a civil government and establish an legal system.

Apparently undaunted by his earlier experience as an apprentice, Dexter continued to print controversial material by authors who were critical of the crown and the church. His printing of The Bloudy Tenet of Persecution, for Cause of Conscience, Discussed in a Conference between Truth and Peace in 1644 cause an uproar. The author was none other than Dexter's friend and correspondent Roger Williams. The book, however, was printed anonymously, without the name of the author, printer, and location. These omissions and the content raised the ire of the Presbyterian Party, which led to Parliament ordering the book to be burned by the public hangman. Since all or most copies had been sold or burned, a second edition of the work appeared with the title changed to The Bloudy Tenent. Regardless who printed the second edition, Dexter was already in hot water with the authorities, which led to life-changing circumstances for him and his wife, Abigail. As Bradford F. Swan, a former arts and drama critic for the Providence Journal and author of Gregory Dexter of London and New England: 1610-1700, wrote, in 1946:

Dexter and his wife Abigail were both imprisoned for printing pamphlets deemed subversive by the House of Lords and the House of Commons. His presses and printing equipment were seized in a raid by the Crown's Stationer's Company on February 5, 1644 which left the Dexters without the means to continue their business in London. Dexter traveled to New England later that year, where he joined Roger Williams and was given a five-acre lot at Providence Plantations.

There is no record of whether Dexter and his wife accompanied Williams on his voyage to Boston with two or three other families in September 1644 or whether they arrived later. One of the first things Dexter did when he arrived in Providence in 1644 was join Williams’ Baptist church. Since there wasn’t much promise of continuing his career as a printer in colonial Providence, he limited his work as a printer to helping Samuel Green of Cambridge Press, in neighboring Massachusetts, to print an annual almanac for several years. He refused payment for this service and requested instead that they send him a copy of the annual almanac each year.

After returning to Providence with his Patent, Williams set out to form the Providence Plantations government. While Portsmouth and Newport were previously part of the Massachusetts Bay Colony government, the towns’ leaders had gained experience in governing. But Providence lacked a body of experienced citizens who could govern, so Gregory Dexter arrived in Providence at an opportune time. His knowledge of government and experience as an accomplished London printer made him a perfect fit for joining Roger Williams and his brother Robert, as well as other prominent Rhode Islanders, in forming a government.

By 1647, Dexter had become active in the colony’s civic affairs and went on to hold many offices and titles during his long life. His first role was commissioner of the committee to form a united government, combining Providence, Warwick, Portsmouth, and Newport. This new government emerged in 1648 and Dexter served on the General Court of Trial until William Coddington received a commission from England in 1651 and became governor of Portsmouth and Newport until 1654.

Dexter then served as town clerk of Providence in 1648 and concurrently as president of Providence and Warwick from 1653-1654. It was as president that Dexter’s connection to Pawtuxet began when he dealt with ongoing land disputes among contesting parties in and around Pawtuxet, which also included litigation with the Massachusetts Bay Colony over who had jurisdiction in Pawtuxet.

Another dispute ensued in 1656, when Dexter became involved in the case of Richard Chasmore of Pawtuxet, who allegedly committed a crime involving a cow. This event caused a rift in the long-standing friendship between Williams and Dexter. For Williams, the issue was not so much about the crime as it was about who had jurisdiction in the case—Massachusetts Bay or Rhode Island? Pawtuxet was still technically subject to jurisdiction under Massachusetts Bay, which already was a sore point with the government in Providence. Perhaps the seed to the disputes had already been sown when Williams sold land to William Harris and William Arnold in 1638.

Although two Narragansetts witnessed the crime, Chasmore’s neighbors denied knowledge of it. Williams consequently wrote to the authorities in Massachusetts to query how they would proceed with this case, as well as with other offenses committed by Pawtuxet residents. During the negotiations, Chasmore fled to a Dutch settlement but soon thereafter appeared at Williams’s house in Providence and surrendered to authorities.

This situation put Williams in a delicate position, but he devised a plan to delay bringing Chasmore to trial in Providence. Because Pawtuxet still fell under the jurisdiction of Massachusetts, Williams didn’t want to jeopardize his efforts to return Pawtuxet to the jurisdiction of Providence Plantations. Consequently, Williams then decided to put Chasmore at the mercy of a general court in Newport the following spring, when the question of jurisdiction could be settled by Massachusetts' officials.

Chasmore then denied he was a Pawtuxet resident and therefore was entitled to a trial under the jurisdiction of Providence Plantations. Yet Massachusetts sent two officers to Providence to arrest and return him to the Bay Colony. In protest, the men of Providence held an unofficial town meeting the same night to prevent handing Chasmore over to Massachusetts authorities.

Much to Williams’ surprise, his old friend Gregory Dexter stood and passionately argued that Pawtuxet was indeed part of Providence Plantations and demanded that the Providence constable bring Chasmore to Newport for imprisonment.

Williams responded by filing charges against Dexter and five others, including his own son-in-law, John Sayles, for being “ringleaders of factions, or new divisions,” which violated colonial law. In the end, Williams failed to appear in court and the charges were dropped.

Gregory Dexter: A Controversial Man in London and Pawtuxet

Part Two

As contentious as the Chasmore case was at the time, Dexter later played a more controversial role in land disputes with Pawtuxet landowners, or the “Pawtuxet Purchasers,” which originated at the time of the agreement to form a government in Providence. These disputes focused on how the original landowners of the colony would deal with the land the Narragansetts had granted them. Williams argued the land should be held in a trust to be shared by the landowners as well as with whoever came to the colony for refuge and were approved by them. Yet some landowners considered this land as their own property from which they could profit as they saw fit.

As a compromise, Williams consented to provide a portion of the land in the original grant. This portion happened to be Pawtuxet but no one had thought to set defined boundaries for the land. This oversight did not become a problem until two events occurred. In 1658, when Massachusetts ceded jurisdiction over Pawtuxet to Providence, the title to the land still went to the original landowners, their heirs, or to anyone who had purchased the land in the interim. A year later, the General Assembly granted Providence permission to landowners to remove any Narragansetts still living within Pawtuxet and to purchase more land up to 3,000 acres bordering it.

Providence landowners failed to use this permission to buy more land, but William Harris of Pawtuxet wasted no time in exploiting the opportunity. Almost immediately after the assembly’s decision, he pursued acquiring deeds from the Narragansett sachems to a large tract of land that followed the Pawtuxet and the Woonasquatucket Rivers 20 miles inland. However, these were not actual deeds of sale; they were confirmation deeds, which gave the landowners of Providence and Pawtuxet the title to the lands yet granted only limited use of the land under the original grant. For example, if their cattle had strayed beyond the town boundaries, it would not be considered trespassing.

Harris recognized the loophole and immediately pounced. Instead of obtaining three confirmation deeds adding 3,000 acres to the town, his acquisitions totaled to 300,000 acres. In addition, his deeds used beguiling language pertaining to how the land could be used. Simply put, the landowners could do whatever they saw as an appropriate use for the land.

Heated debate followed at a crowded town meeting in March 1660, when the town mandated the western boundaries set at 20 miles. Harris argued for a different configuration in the form of a dividing line between Pawtuxet and Providence, which would transform Pawtuxet into a huge parcel of land westward between the Pawtuxet and the Woonasquatucket Rivers.

Williams and Dexter condemned Harris’s efforts on moral grounds, not only what they perceived as an act of a greedy land grab but also as a betrayal to the Narragansetts. Williams especially had always sought to maintain an honest relationship in dealing with them and strongly believed in allowing the indigenous population of the colony to keep their land unless they sold it. He criticized colonists who believed they could appropriate land from the Indians by arguing they didn’t have property rights.

Arthur Fenner of Providence also joined Williams and Dexter in opposing Harris in what became a drawn-out, acrimonious battle, which raged in and out of court and at town meetings for the next 20 years. Although Harris filed multiple lawsuits and won most cases, he was left empty-handed because the decisions hadn’t been executed for whatever reasons. The wrangling between Harris and the Providence faction became even more heated as Dexter, Fenner, and Williams employed various strategies to counter his efforts by either delaying, blocking, or ignoring Harris’s efforts to expand the land boundaries.

In the interim, Williams sailed to England and obtained, in 1663, from King Charles II the Royal Rhode Island Charter, officially recognizing the Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations. Dexter’s name is also among the Providence citizens mentioned in the charter.

Providence attempted to quell the land dispute in 1665 by agreeing to a dividing line to Hipses Rock in today’s Johnston, RI, which was one of the original boundaries granted by the Narragansetts, but the gesture provided Harris no real compromise. At the same time, a determined and litigious Harris had become embroiled in other lawsuits against landowners in Warwick, as well as in Pawtuxet, for what he viewed as trespassing on his private property. Despite filing his many lawsuits successfully, Harris again failed to see results other than arbitration or abeyance.

Harris had traveled to England in 1675 to appeal to the King in Council. The king in turn granted the petition and commanded the governors of New England’s four colonies to hear the cases, with jurors selected from each colony. Due to King Philip’s War, the special court could not begin hearings in Providence until July 1677.

The townsmen of Providence chose Williams, Dexter, and Fenner to answer to Harris’s charges, which the town approved in August 1677. In October, Harris and Thomas Fields filed more charges against Dexter and Fenner. Once again Williams, Dexter, and Fenner replied for Providence. This time, Harris changed his original charge that instead of purchasing the land from the Narragansetts, he argued that he bought the land from Williams for £20, but then contradicted himself again by stating the land was given to him. The court sided with Harris and awarded him £2 to be paid by Dexter, Fenner, and Providence, plus court costs, but Dexter and Fenner appealed.

The dispute wore on concerning Pawtuxet’s exact boundaries. When Fenner questioned Harris about which landmarks and measurements constituted the boundaries, Harris was unable to answer fully and requested arbitration. Fenner then engaged a surveyor to determine the boundaries to settle the issue. According to the surveyor’s report, Pawtuxet gained little land from that which Harris had imagined. Harris protested, but the Rhode Island contingent of the special court refused to participate because a member from Connecticut was absent. The remaining members of the court then decided to refer the case back to the king. Harris had been thwarted again.

Still determined and bitter, Harris sailed to England to petition the crown once more in 1679, which was successful. The Rhode Island governor and his council ruled against Fenner, Dexter, and Providence, and levied a fine awarded to Harris, including court costs. At the same time, Harris failed to resolve the question of the Pawtuxet dividing lines.

Harris sailed for England once again, but the ship apparently didn’t sail directly to England because it was captured by Barbary pirates. Harris was enslaved in Algiers for two years before his ransom was paid. Three days after his arrival at a friend’s home in London, Harris died in 1681.

Even after Harris’s death, the rancorous battle for Pawtuxet’s lands persisted for some years but eventually petered out. It seems that some family members and descendants of the quarreling parties chose to pursue other interests and even intermarried. As Shakespeare wrote, “All’s well that ends well.”

Sources:

Newman, C.S. Genealogy of the Dexter Family 1610-1857. Providence, RI. (1857).

Swan, Bradford F. Gregory Dexter of London and New England: 1610-1700. Rochester, NY: Printer’s Valhalla (1949), 115 pp.

Diverse genealogical and historical online sources.

Super interesting! Maybe you have the beginning of a historical novel here.

Very interesting read which got me looking up that rock and finding information about a Native American soapstone quarry in RI, hiking trails in RI, and the tribes that lived there.

However, I still wonder about the cow.